Secondary dominant chords play a key role in music by adding unexpected color and tension that enrich the harmonic landscape. Unlike the basic dominant chord built on the fifth note of a scale, secondary dominants temporarily tonicize chords other than the main key center, opening up new possibilities for movement and expression.

At Skoove, we believe that mastering secondary dominant chords is essential for anyone looking to elevate their piano playing or songwriting. These chords introduce exciting twists to familiar progressions, making your music sound more vibrant and dynamic.

In this article, you’ll discover what secondary dominant chords are, why they’re so important, and how they enhance music by creating richer, more compelling harmonies.

- Fall in love with the music - Learn your favorite songs, at a level suitable for you.

- Enjoy interactive piano lessons - Explore courses covering music theory, technique chords & more.

- Get real-time feedback - Skoove's feedback tells you what went well and what needs practice.

What is a dominant chord?

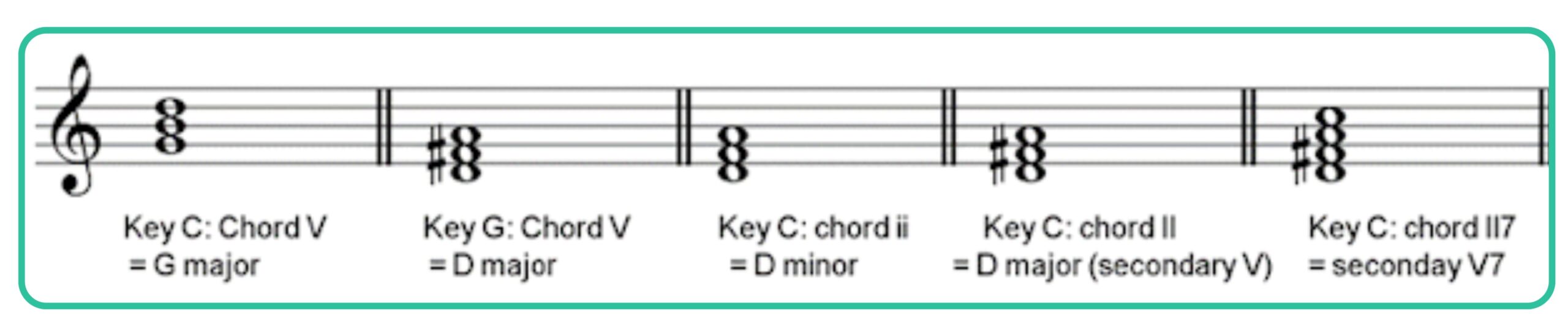

To understand secondary dominants, we first need to look at dominant chords. A dominant chord is built on the fifth note of a scale. That’s why it’s often called the V chord. In the key of C major, that’s a G major chord.

When you add one more note,a minor seventh to that G chord, you get a dominant seventh chord, written as G7. This chord creates tension that feels like it wants to go somewhere, usually back “home” to the tonic chord, which is C major in this case.

This feeling comes from a special note inside the dominant chord called the leading tone. It’s just one half step away from the tonic and gives that strong pull back to the root. That pull is what makes dominant chords so important in harmony.

If you’re still learning the basics, make sure to reviewmajor and minor chords and how they function in different keys.

What are secondary dominant chords?

While dominant chords are essential, secondary dominants offer a powerful way to spice up harmony. As their name suggests, they behave like dominants but resolve to a chord other than the tonic.

For example, in C major, the main dominant chord is G7, which resolves to C. But a secondary dominant like D7 resolves to G, which then resolves to C. It creates a beautiful chain of tension and release, making harmony more expressive.

You’ll see secondary dominants used all the time injazz chords and other styles where colorful harmony is key. They’re especially effective when combined withchord inversions to create smooth voice leading.

How to build secondary dominant chords?

Let’s look at how to build a secondary dominant chord, using the key of C major as an example. One of the most common secondary dominants is called the “five of five,” written as V of V or V/V.

First, we find the fifth degree (V) of the C major scale. Counting up from C, the notes are D, E, F, G. So, G is the root of the V chord in C major.

Next, we find the fifth degree of the G major scale, because we want the dominant of G. Starting on G, count up five notes: G, A, B, C, D. The fifth note is D. This means D (or D7 if we add the seventh) is the secondary dominant—V of V—in the key of C.

Adding the seventh note to this chord is common and helps to create a stronger dominant sound. That’s why you’ll often see it written as D7 instead of just D.

Important tips when building secondary dominants

- This method doesn’t work for the seventh degree of the scale. That’s why you won’t find a V of vii chord as a valid secondary dominant.

- If your secondary dominant chord sounds like a chord already in the key, you should add the seventh to make it clear it’s a dominant chord and not just a regular chord from the scale.

How to use secondary dominants in music?

One of the main reasons musicians use secondary dominants is to add suspense, tension, and surprise to their music. When writing music and thinking about harmony, we are always looking for ways to make it more interesting. Secondary dominants help with that.

By introducing a secondary dominant chord, you give the listener something unexpected that grabs their attention. This little twist can make a song more exciting and keep it feeling fresh.

For example, the jazz standard “Fly Me to the Moon,” famously performed by Frank Sinatra, uses many secondary dominants to create its rich, colorful sound. You can hear A7 leading to Dm, then D7 leading to G, and G7 resolving to C. These chord moves add a smooth, jazzy tension and release that perfectly illustrate how secondary dominants work in real music. This example is perfect if you want to hear how secondary dominants add excitement in a jazz context.

How to find secondary dominant chords?

The hardest part of spotting secondary dominants is confirming the main key first. Since secondary dominants are not part of the key (they’re non-diatonic), they can make identifying the key trickier.

When you analyse a chord progression, if a chord doesn’t fit the key, check if it’s a V chord leading to another chord within the key. That’s likely a secondary dominant.

Chord progressions using secondary dominants

Secondary dominants add excitement and color to chord progressions. They bring in notes that don’t normally belong to the main scale, which makes the music more interesting.

For example, in the key of C major, adding a D7 chord introduces an F♯ note, which is not in the C major scale. This surprise note can grab the listener’s attention and make the music stand out.

Here are some common chord progressions that use secondary dominants:

- C – Am – D7 – G7 (V/V)

- C – G7 – A7 – Dm – G7 (V/ii)

- C – Am – G7 – C – E7 – Am (V/vi)

- C – F – G7 – C – B7 – Em – Am (V/iii)

Secondary dominants add tension, color, and movement to your chord progressions. By learning how they work, you can make your music sound more expressive and interesting. Try adding them into your songs and see how they transform your sound. At Skoove, we make it easy to explore these chords through fun, step-by-step piano lessons that help you bring music theory to life.

Author of this blog post:

Eddie Bond is a multi-instrumentalist performer, composer, and music instructor currently based in Seattle, Washington USA. He has performed extensively in the US, Canada, Argentina, and China, released over 40 albums, and has over a decade experience working with music students of all ages and ability levels.